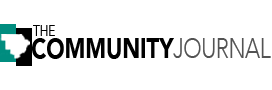

I do not remember a time when I did not know about Chief Oceochemathla. In our stories he was handsome, charming, and brilliant. His village at “The Forks” was prosperous: a place of trade, wealth, rest, and refuge. But, on a fall night he and his people were surrounded by an army which included John Coffee and Davy Crockett. These men watched the people through the night. In the morning soldiers entered an empty village in which fires were still burning, and food sat on tables.

They escaped what would have been a massacre. How this had been managed had been forgotten. What was remembered is that the people had taken an oath to return to The Forks. The following is the result of my search to prove my family’s story and the discovery of how the Creeks actually escaped.

On the evening of October 12, 1813, 800 volunteers with the Tennessee Militia, led by General (then Colonel) John Coffee and frontiersman Davy Crockett, approached and surrounded Black Warrior Town. The soldiers camped on the surrounding ridges and watched as the Creeks (and some Cherokees and Choctaws who had taken refuge) went about their evening business. The plan was simple: surround the village center and draw the warriors into a conflict. The same tactic worked weeks later in the Battle of Tallushatchee and the Battle of Talladega. However, this strategy would not work in Black Warrior Town.

Black Warrior Town, which is translated from the word, Tuskaloosa, was the northernmost settlement of the Muskogee (Creek) Nation. The town center was situated on the eastern side of the confluence of the Sipsey and Mulberry Forks (in present day Walker County) which join to make the Black Warrior River north of Locust Fork. The present day communities of Campbellsville, Dilworth, Coon Creek, Pineywoods, and the town of Sipsey now occupy the territory Black Warrior Town once controlled. Another name this area had was Apotaka Hacha, meaning border-river, as it divided the territories of Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Creek. According to Erey Williams, whose family told stories of Black Warrior Town, the area around what is now known as The Forks was considered sacred.

Prior to October of 1813, Black Warrior Town served as the main Creek village on the Sipsey and Mulberry Forks, with as many as four minor villages surrounding it. The Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Cherokee, among others, came to the town to make deals with the Creeks and rest from hunting. Using the various tributaries of the Black Warrior, people traveled to and from the town.

Aside from the waterways, there were other roads that converged in Black Warrior Town. One ran north and south and was known as The Path of the Black Warrior or Black Warrior Trace. This route connected the Native Americans living in the valleys of the Tennessee and the Chattahoochee rivers with those of the Black Warrior. Known to settlers as Mitchell’s Trace, the road passed through Melton’s Bluff in Lawrence County. Today this road is known as Old Town Road which locals know is in reference to the “Old Indian Town.” Another road ran east and west from South Carolina to the Chickasaw Nation. Still another ran northeast to southwest and originated at Ditto’s Landing near Huntsville and terminated in Black Warrior Town.

Although the town’s center was situated on the east side of The Forks, the village was much larger and consisted of many log structures. During the colder months, the Creeks lived on the ridge tops in log houses. For the summer they had more open structures built on stilts to accommodate changing water levels on the river bottoms of the Mulberry and Sipsey Forks. They farmed fish in ponds dug at the edge of the river bottoms against the steep bluffs. These ponds would be replenished during seasonal flooding. Corn, squash, and beans grew in abundance on this fertile land.

Such was the situation during those early days of the 1800’s; Black Warrior Town thrived. It was a place where people raised families, grew crops, cured sickness, told stories, and buried the dead.

However, circumstances changed swiftly after 1811. During that year the Shawnee warrior chief, Tecumseh, visited Black Warrior Town. It is well-known that Tecumseh made his way through many Creek towns arguing for all Native American tribes to unite and join forces with the British Army against the United States. Although little is known of his discourse with the local Creeks, Tecumseh’s persuasive personality along with his claim that he would cause a great earthquake and its subsequent fulfillment in the disastrous New Madrid earthquakes would have most certainly made a great impression.

It is under these circumstances that a dynamic leader emerged in Black Warrior Town, Oceochemathla. It is his name that has made it into the folklore surrounding the Sipsey area. He is one of the two known chiefs in the town. The other was sometimes called Black Warrior or Little Warrior, and he was the older of the two. It is likely that Black Warrior was the micoand Oceochemathla was a micalgi. Oceochemathla dealt diplomatically with the local tribes and with settlers. However, he could be duplicitous with those whom he knew meant his people harm.

Oceochemathla along with a few warriors would travel from Black Warrior Town to St. Stephens (a trading post on the Tombigbee) twice a year to trade deerskin and various pelts for other goods. Colonel George S. Gaines, a government agent who served the Choctaw, would allow him roughly $100 in credit which he would pay during the next visit. In 1811 he arrived at St. Stephens with forty warriors in “well provisioned” canoes. This was alarming for Gaines because there were only seven white men and fewer enslaved males at the trading post. On this trip he wanted $1000 in credit for he and his warriors.

Over the years Oceochemathla had struck up a friendship with Tandy Walker, a well-known blacksmith, who was also at St. Stephens on this occasion. The chief revealed his plans of fighting with Tecumseh and the British against the United States to Walker, even asking the blacksmith to join them. Walker “maneuvered” himself out of the situation. Gaines made excuses and did not allow the men the $1000 in credit.

Black Warrior Town “figured prominently in the increasing tensions that led to the Creek War of 1813–1814”. This was due in large part to the kidnapping of a white woman. While on a return trip from visiting with Tecumseh in April of 1813, a group of Warriors from Black Warrior Town took a white woman, Martha Crawley, prisoner after killing other people at her home in Tennessee. The official report is that Tandy Walker rescued Mrs. Crawley. However, other reports state that one of the chiefs ordered the warriors to take the captive to Walker. Regardless, her kidnapping was used to incite the settlers against the Creeks.

It is that summer of 1813, while Martha Crawley was yet to be returned to her family, that the Creeks attacked Fort Mims shortly after the Battle of Burnt Corn Creek. Fort Mims was a rallying call for those who wanted to expel the Creeks from the territory. It is in this fractious climate that General Andrew Jackson dispatched the Tennessee Militia, a force of approximately 800 men, with the purpose of taking vengeance for Fort Mims.

James Robertson, a Chickasaw Indian agent with twelve Chickasaw rangers had orders to find “Little Warrior’s Town” (Black Warrior Town) because it was thought to be a staging area for planned raids on the Tombigbee settlements. It was to be a reconnaissance mission. Robertson reports on September 23, 1813: “…the Little Warriors town, on the Black Warrior river, which I apprehend most danger from as it is the place where the rebellious Creeks hold their Council + War dances of late.” There is no report Robertson ever reached the town.

According to local legend, just before dawn on October 13, 1813, the 800 members of the Tennessee Militia entered Black Warrior Town after watching the sleeping village through the night. The soldiers began ransacking the town. They were disturbed by the eerie silence. Fires were still lit in the homes. In some cases, cooked food sat out waiting to be eaten. However, every man, woman, and child were gone. Oceochemathla had gotten his people out from under the noses of the well-seasoned Colonel John Coffee and arguably one of the United States’ best trackers, Davy Crockett.

In order to ensure Crockett’s aid in this endeavor, Andrew Jackson had promised to grant him a substantial amount of land. Once the Native Americans disappeared, the way was open for Crockett to make his claim. He chose the land atop the bluff that rises just above The Forks. This is directly behind the present-day location of T&R Grocery. Local legend has it that Crockett liked the view and planned to build a house there. However, he would never enjoy that land; he would never build a house there. Something happened to Davy Crockett regarding Black Warrior Town; something that made him to decide to never return.

The Tennessee Militia raided the stores of food the Creeks had set aside. It was after all, October, and the crops had been harvested. The soldiers took 300 bushels of corn along with dried beans. Aside from the meat they had to kill along the way, the vegetables of Black Warrior Town sustained them for over a year.

General Coffee ordered the town burned, just as he had the two villages before it. He did not want the natives to have anything to which they could return. The militiamen set fire to the town and surrounding areas. As the log homes and council house burned the order had come to take anyone alive that might be there. Coffee needed intelligence, and dead men do not talk.

For years the story ended there for my family. No one had the knowledge of how the entire village plus refugees escaped. Then I had the fortunate opportunity to speak to Roy Pounds, a local amateur historian and member to the Echota Cherokee of Alabama who has since passed away. He related the following to me.

It is during the burning that the elder chief, Black Warrior/ Little Warrior and five older men were flushed out of the woods. They had volunteered to stay behind. The previous night they had gone from house to house stoking the fires, so it would appear that the people were still there. They sacrificed themselves, so the rest of the people could escape.

A young member of the militia had his gun pointed at the old chief. Others would say the chief recognized the young man who may have been of mixed blood. He shot the old chief. It is believed that this man may have led the militia to the town. He is buried very near the site where he murdered Black Warrior/ Little Warrior.

Accounts agree that Oceochemathla had worked tirelessly to prepare for such an event. Roy Pounds added that canoes had been outfitted with supplies and pulled underneath the bluffs that ran along what is now known as Burton Bend (a crook in the river after The Forks). It is said he had a place prepared near what is now know known as Cordova, further down the river. As they camped on that first night, the smoke from their town traveled funneled by the river. And so, they watched as the remains of their homes passed.

In both my family’s memory and in Pounds’ information the survivors made a solemn oath; they would return to the place where the rivers come together, and if they could not, their children would. The beginning of the border river was sacred; it had “power” that had to be protected.

Although it does seem that all the inhabitants left together, it does not appear that they stayed together. After all, the plan was to meet back once things were safe. Some traveled to Andalusia, met with other Creeks, and eventually joined the Seminole. Others wound up in Talladega. Some went further west. And some stayed. They melted into the hills. These stories are familiar to several families in the area. These involved ancestors who went into the bluffs and stayed hidden. They ate roots and berries to prevent starvation, and they waited and scavenged and survived. And although it took time, years, and in some cases a generation or two, they made it back to the ashes of Black Warrior Town because they had taken an oath to do so.

One question that remains concerns Davy Crockett. Why did he not return to claim his land and build that house that he wanted overlooking the confluence of the Mulberry and Sipsey Forks? Local legend has an answer that can be supported in part by historical records.

In 1816 Crockett became critically ill while exploring the area around the Black Warrior River. It is possible he had contracted malaria. It is the belief of the locals that he was very near Black Warrior Town when he fell ill, perhaps even scouting where he would build his new home on the land he would receive from serving Andrew Jackson.

He was found by “Indians” who helped him to the cabin of Jesse Jones. It was there that Mrs. Jones gave Crockett Bateman’s Drops. This particular drug was popular at the time, and it contained both alcohol and opium among other things. [32] The drug threw Crockett into a sweat, and he was delirious for five days. He was so sick that his wife was told he had died.

It is during this delirium that legend says he found himself on the bluff above The Forks. He was alone there except for a Creek girl. “You don’t belong here,” she told him. “This place isn’t meant for you. It’s ours.”

“What does it matter? Your people are gone,” Crockett replied.

“No,” she smiled. “We remain.”

Crockett was so rattled by the vision that he never claimed the land. Moreover, when asked how to get to Black Warrior Town, he gave incorrect directions. He placed the town near present day Tuscaloosa.

For years Black Warrior Town remained buried under the ashes of its burning. Time has passed, and communities have both risen and fallen. Coal mining has come and gone. The Forks remains a traditional gathering place. Stories about Oceochemathla and the escape are still told. Sometimes the old families discuss other more mystical things, topics not for public discourse.

“You can’t tell anyone what we talk about here,” Fairy Parnell Bridges said, quoting her father, Alpha Pettus Parnell. “Because they will come, and they will take everything you have, and they will send you away.” Even so, the area known as Black Warrior Town has a storied past that that demands to be told.

Bibliography

Alexander, Lawrence S. 1982. Phase I Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Oliver Lock and Dam Project Area, Tuscaloosa County, Alabama. Prepared for United States Army Corps of Engineers, Mobile District, Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Office of Archaeological Research, The University of Alabama.

Auburn University. 2018. “Water Resources Center.” Black Warrior River Basin: History.Accessed November 3, 2018. http://aaes.auburn.edu/wrc/resource/rivers-of-alabama/black-warrior-basin/history/.

Bridges, Fairy Parnell, interview by Lolly Parnell Aaron Martha Parnell Salomaa. Before 1990. Alpha Pettus Parnell Confesses

Clinton, Matthew William. 1958. Tuscaloosa, Alabama — Its Early Days 1816–1865. Tuscaloosa: The Zonta Club.

Crockett, David. 1834. Narrative of the Life of David Crockett, of the State of Tennessee.Philidelphia: Carey, Hart & Co.

Gillespie, Loretta. 2015. “Melton’s Bluff.” The Moulton Advertiser, April 23.

Jones, Randell. 2006. In the Footsteps of Davy Crockett. Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John E. Blair.

Lewis, Jim. 2014. Lost Capitals of Alabama.Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press.

Manasco, Jim. 1995. “The Early History of Walker County; Part Three: The Creek Indian War, 1780–1814.” The Daily Mountain Eagle, April 9: A12+.

Maxwell, Thomas. 2016. Washington County, Alabama Genealogy Trails, St. Stephens Records. Accessed January 29, 2019. http://genealogytrails.com/ala/washington/ststephens_1.html.

Parnell, Barbara Ann McClendon, interview by Martha Parnell Salomaa. Before 1979. Histories from the McClendon/Tidwell/Parnell families (June 12).

Parnell, Essie Williams, interview by Martha Parnell Salomaa. Before 2003. Histories from the Williams/Parnell Family(August 3).

Pounds, Roy G. 2011. Flat Rock or Not.Cordova: Lulu Publishing.

Pounds, Roy, interview by Martha Parnell Salomaa. 2018. The Invasion of Black Warrior Town (July 31).

Sterling, Robin. 2018. Tales of Old Blount County, Alabama. Lulu.

Williams, Erey Amoel Lewis, interview by Martha Parnell Salomaa. Before 2006. Histories from the Lewis/Williams Family(December 2006).

Wood, Karen G. 1988. From Tuscaloosa to Squaw Shoals: A History of Holt Lake, Alabama. Archival Study, Athens, Georgia: Southeastern Archeological Services, Inc.

Young, Beth. 2002. “Black Warrior and Cahaba.” Citizen Guide to Alabama Rivers 6–7. Accessed December 18, 2018.

Martha! That was so here interesting. I love to hear about history, and of course hearing about local history is even better.

Before he passed, my mom was a home health aid to Carl Elliott. I had performed a speech in school about the homeless in Birmingham and had done very well on it, and was asked to perform for other classes. When mom told Mr. Elliott about my speech, he asked if I’d so kindly come by and perform the speech for him. I was nervous, but did the best job I’d done so far there at the foot of his bed. He asked to give me a hug and gave me 2 books on his history of Walker County, which he signed, of course. I have read and re read those books so many times over the years, never tiring of the part where he speaks of ” John Dan Myers, a man of keen intelligence land high principals “– which is my paternal great-great grandfather.

Daddy used to find so many arrowheads when he was young, he said if the pieces weren’t complete he wouldn’t even keep them! He cut out a big board in the shape of Alabama and painted it. He glued those arrowheads to the board, with some obvious spear points. And you know where I grew up /he grew up so it was all through there. Steve and I have boxes we found on his family ‘s land in Phil Campbell.

This story seems to have a bit of a mystery to it and was very well written, of course. I’d love to read anything else you’ve written on the area. Great job!